teaching trade union history in a post-labour age

It's week 11 of my 2nd year undergraduate history module, 'Peace, Power & Prosperity: British Society, 1789-1914'.(1) This week's lecture and seminar were on 19th century trade unions and labour history.

What made this week's session interesting, and perhaps important, because the UCU have called a marking boycott. This has completely riled the students. There has been an awful campaign on twitter #markmywork. and it appears that the student union from my university seems to be leading the campaign. For a good summary of the campaign and a justification of the strike, read this academic's response: http://plashingvole.blogspot.co.uk/2014/04/mark-my-work.html

But the history of trade unions can be very hard to teach today.

Teaching labour history to undergraduates, most of whom are aged 19-20, is made difficult because most students have no frame of reference regarding trade unions.

Trade unions just don't figure in their lives or family histories. Many of our students are sons and daughters of the working-class done good during the 80s and 90s - the East End plumbers, electricians and builders who managed to do well, sell their council house, and move out to new-build private housing estates in the Tory heartlands of Essex. The quashing of the power of the trade unions by Thatcher's government, and New Labour's ditching of clause 4 and its move away from its socialist roots, combined with mass de-industrialisation and the rise of unsecure hourly-paid jobs, workfare, etc etc, has created a post-labour age in which unions seem an anomaly to many people.

Many of the students, when asked, have never been in a demonstration before (this also comes through in my other module on the history of popular protest). They have never seen a picket line. It seems historical to them.(2)

So the first thing I do when teaching 19th Century trade union history is ask the students what they think a trade union is and what it stands for. They've no idea, other than trade unions cause 'disruption'.

Note this is just one week in a 12-week module that covers all sorts of topics (empire, leisure, reform, family, urbanisation etc), so there's a lot to pack in. I go through the standard interpretation of what they stood for in the 19thc - defence of skilled (male) labour against free-market laissez-faire economics, unskilled (female/child/non-apprentice/machine) labour. I then chart what now seems like a really old-fashioned timeline of events and people that perhaps would have been bread and butter to the WEA classes that E. P. Thompson used to teach in the 50s and 60s, but are almost forgotten outside the trade union movement today:

But again, this seems somewhat outdated, and I worry that it perpetuates the idea among the students that trade unions are historical and no longer relevant. I also worry that I would appear to be the crazy leftie academic that their parents warned them about, when I'm far from that.

Sample questions from the students this week included, 'what type of people joined up to trade unions?, (answer: um, workers...);

'Trade unions were those things that had loads of power and stopped the country from working. When was it that Margaret Thatcher got rid of their power?' (answer: you're thinking of the miners' strikes of 1984-5).

But there was some light at the end of the tunnel. After looking at Sonya Rose's article, ‘Gender antagonism and class conflict: exclusionary strategies of male trade unionists in nineteenth-century Britain’, Social History, 13: 2 (1988), the seminar discussion moved on to the issue of women's rights and equal pay.

One of the students asked the good question about when did trade unions move away from trying to protect men's interests and start campaigning for equal pay, and the class's interest increased when I suggested not until the 1960s, mentioning the Dagenham women's strike. The film Made in Dagenham had struck a chord with the Essex-based students (and note, the majority of the students taking the module are female).

So finally I convinced them that trade unions are still important and relevant to them in some ways. They were also shocked at the fact that the government only instituted minimum wage legislation in the late 1990s; they thought it was much earlier than that, especially when I had been talking about the weavers' petition for a minimum wage back in 1808.

The issues that seem to matter most to the students were low pay, insecurity, zero-hours contracts, and gender discrimination. They still don't quite see the role that trade unions could play in helping fight these, but perhaps they will soon.

(1) note the title isn't mine - I inherited the module from one of my predecessors, possibly Matthew Cragoe.

(2) a startling memory for me is of a previous UCU strike, when the students driving into campus had no idea what we were doing when we stood across the entrance to the carpark with banners etc. They just had no idea what a picket line was or what it was for.

|

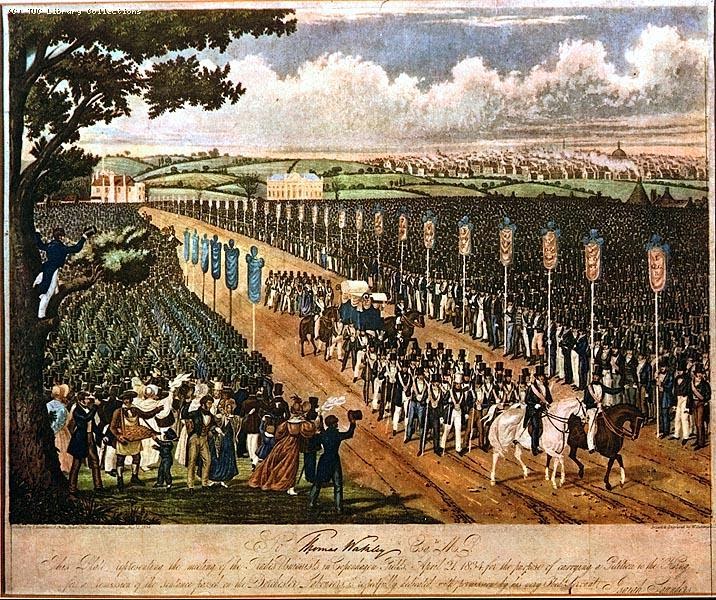

| http://www.unionhistory.info/timeline/Tl_Display.php?Where=Dc1Title+contains+%27Copenhagen+Fields+Demonstration%27+ |

What made this week's session interesting, and perhaps important, because the UCU have called a marking boycott. This has completely riled the students. There has been an awful campaign on twitter #markmywork. and it appears that the student union from my university seems to be leading the campaign. For a good summary of the campaign and a justification of the strike, read this academic's response: http://plashingvole.blogspot.co.uk/2014/04/mark-my-work.html

But the history of trade unions can be very hard to teach today.

Teaching labour history to undergraduates, most of whom are aged 19-20, is made difficult because most students have no frame of reference regarding trade unions.

Trade unions just don't figure in their lives or family histories. Many of our students are sons and daughters of the working-class done good during the 80s and 90s - the East End plumbers, electricians and builders who managed to do well, sell their council house, and move out to new-build private housing estates in the Tory heartlands of Essex. The quashing of the power of the trade unions by Thatcher's government, and New Labour's ditching of clause 4 and its move away from its socialist roots, combined with mass de-industrialisation and the rise of unsecure hourly-paid jobs, workfare, etc etc, has created a post-labour age in which unions seem an anomaly to many people.

Many of the students, when asked, have never been in a demonstration before (this also comes through in my other module on the history of popular protest). They have never seen a picket line. It seems historical to them.(2)

So the first thing I do when teaching 19th Century trade union history is ask the students what they think a trade union is and what it stands for. They've no idea, other than trade unions cause 'disruption'.

|

| http://www.unionhistory.info/timeline/1880_1914.php |

Note this is just one week in a 12-week module that covers all sorts of topics (empire, leisure, reform, family, urbanisation etc), so there's a lot to pack in. I go through the standard interpretation of what they stood for in the 19thc - defence of skilled (male) labour against free-market laissez-faire economics, unskilled (female/child/non-apprentice/machine) labour. I then chart what now seems like a really old-fashioned timeline of events and people that perhaps would have been bread and butter to the WEA classes that E. P. Thompson used to teach in the 50s and 60s, but are almost forgotten outside the trade union movement today:

- the Combination Acts of 1799-1800

- Tolpuddle Martyrs of 1834

- Robert Owen

- Plug strikes of 1842 and Chartism

- new model unions from the 1860s onwards

- Bryant & May women matchworkers' strike 1888

- London Dock and Gasworkers' Strike of 1889

- formation of the ILP and Labour Representation Committee and Keir Hardie

- 1901 Taff vale case

- historiography: Webbs and Hammonds, Hobsbawm and Thompson

But again, this seems somewhat outdated, and I worry that it perpetuates the idea among the students that trade unions are historical and no longer relevant. I also worry that I would appear to be the crazy leftie academic that their parents warned them about, when I'm far from that.

Sample questions from the students this week included, 'what type of people joined up to trade unions?, (answer: um, workers...);

'Trade unions were those things that had loads of power and stopped the country from working. When was it that Margaret Thatcher got rid of their power?' (answer: you're thinking of the miners' strikes of 1984-5).

|

| http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/politics/g8/source/g8s1a.htm |

But there was some light at the end of the tunnel. After looking at Sonya Rose's article, ‘Gender antagonism and class conflict: exclusionary strategies of male trade unionists in nineteenth-century Britain’, Social History, 13: 2 (1988), the seminar discussion moved on to the issue of women's rights and equal pay.

One of the students asked the good question about when did trade unions move away from trying to protect men's interests and start campaigning for equal pay, and the class's interest increased when I suggested not until the 1960s, mentioning the Dagenham women's strike. The film Made in Dagenham had struck a chord with the Essex-based students (and note, the majority of the students taking the module are female).

So finally I convinced them that trade unions are still important and relevant to them in some ways. They were also shocked at the fact that the government only instituted minimum wage legislation in the late 1990s; they thought it was much earlier than that, especially when I had been talking about the weavers' petition for a minimum wage back in 1808.

The issues that seem to matter most to the students were low pay, insecurity, zero-hours contracts, and gender discrimination. They still don't quite see the role that trade unions could play in helping fight these, but perhaps they will soon.

(1) note the title isn't mine - I inherited the module from one of my predecessors, possibly Matthew Cragoe.

(2) a startling memory for me is of a previous UCU strike, when the students driving into campus had no idea what we were doing when we stood across the entrance to the carpark with banners etc. They just had no idea what a picket line was or what it was for.

Great article. I have been in a union for 40 years until my trade has diminished (print). I am now working in a call centre and the young ones seem non-plussed on how there holidays and breaks have been fought for. I hope the scottish referendum has awakened this country's youth to participate in politics.

ReplyDelete