Protest history workshop #3, Cheltenham, 2/3/13

|

| TNA, PL 27/9 |

TNA, PL 27/9.

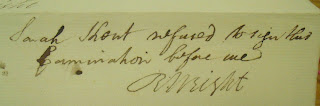

Charged with being at the Luddite attack on Burtons' powerloom mill at Middleton, Lancs, on 21 April 1812, this woman made a defiant act of resistance by refusing to sign the record of her examination by the Manchester magistrate Ralph Wright of Flixton Hall.

But is this protest? Did it work? Can protest be individual? What is the difference between protest, collective action, resistance and opposition?

|

| can we include all types of opposition within the term 'protest'? |

These were questions we had asked at the first workshop on 'new approaches to the history of protest' back in 2011, and returned to last weekend at the third workshop at the University of Gloucestershire.

I started off the day with some reflections on the spatial turn in history (see extended version in my HWPP paper) combined with some questions about the legacy of E. P. Thompson, given that there are so many commemorations of the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of the Making of the English Working Class.

The first session was headed by Iain Robertson, who spoke of the performance of protest in crofting landscapes in the Highlands. He spoke of the sheer physical presence and affective charge of being in place, evoking Nigel Thrift's idea of the 'spatial dance' with other human and non-human actors. Highland resistance took its modes and meanings from work, and work was the protest performance.

Iain was the first of many that day to bring up the issue of memory, and contested memories relating to space and to rights and liberties relating to place. This was even more evident in Simon Sandall's paper on protest in the 17th century Forest of Dean, which raised much heated debate among residents of the Forest about whether the free miners had a right or a privilege (the residents argued the latter). The debate was a reminder of the deep-seated and emotionally loaded sense of place.

David Mead, sandwiched in between this debate on memory and place, gave a contemporary view of the law today, especially in relation to occupation and kettling. His points were highly resonant of protest past and showed the massive continuities in both the law and how it is interpreted and enforced by forces of law and order. Legal constructions define:

- place specific restrictions,

- rights of access,

- ownership,

- space dependent regulation,

- surveillance.

Mead also addressed the issue of public-private places and spaces, as highlighted by Anna Minton and Owen Hatherley in their works about 'malls without walls' and how they restricted protest in seemingly public spaces. Yet he also showed how protests could use spaces to their advantage, as at Greenham Common, where the women were effective because they were out of place.

The second session focused on topography and the phenomenology of protest. Nigel Costley examined West Country protest, particularly the Warren James rising and Tolpuddle. Janette Martin showed how itinerant Chartist lecturers used their journeys and their experiences as a vital part of engaging with the communities they visited and their own perceptions of radical utopias. Steve Poole considered the radical landscapes of 1790s intellectuals, notably John Thelwall's The Peripatetic (1793) - (amusingly categorised on googlebooks as 'sports and recreation').

The third session was a postgraduate focused session, testimony to the new research finally coming through in the history of protest. All were micro-studies, and based on the idea of 'militant particularism'. Paul Griffin talked about the spatial politics of Red Clydeside explicitly within these terms, though also with the combination of internationalism. Ruth Mather charted the Queen Caroline affair in the North West, and how it was expressed as a locally-based movement. Francis Boorman zoomed the focus even further into one street, Chancery Lane in London during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, showing its integral role as sites of radicalism and loyalism.

The final session thought about protest events that might not be categorised strictly as radicalism or even as protest. John Martin considered resistance to the food production campaign during the Second World War in Hampshire. Linking to David Mead's earlier paper about private-public spaces, James Baker examined the innovative and unusual forms of protest during the 'Old Price riots' of 1809, especially in reaction to the increasing number of restrictions placed on the audience during their month long protest to the rise in theatre prices and the installation of private boxes. James mentioned David Sibley's 1995 book, Geographies of Exclusion, which informed, consciously or unconsciously, many of the papers of the day. Nick Mansfield finished with a paper on common soldiers and whether desertion and other actions of the military should be considered as protest and resistance.

Carl Griffin ended the day with a series of questions and challenges for us all:

- after three workshops on 'new approaches to the history of protest', have we found any 'new approaches'? The consensus that was that we need to build on the work of previous historians, but that the 'new approaches' are from the new blood coming into the field.

- are we right to delineate this as 'protest history', when most participants in protest would not have identified themselves as 'protestors' and most historians working on the topic would not categorise themselves as 'protest historians'?

- The conclusion was that there was no one protest history, but lots of good work. In the late 1990s, few scholars would admit they were working on protest and resistance, apart from a few brave souls, but now we have a whole room of scholars and are seeking many more.

Comments

Post a Comment