British Universities by Ernest Barker (1946)

I bought this pamphlet in an idiosyncratic secondhand bookshop in Caterham yesterday. It's called British Universities, by Sir Ernest Barker, published by the British Council in 1946.

It's a fascinating insight into thoughts about what universities were for, and should be, just after the War, and also how they were promoted to the rest of the Commonwealth. The list of other titles available in the series is also intriguing, and I would love to find more of these pamphlets, especially to compare their language and ideas with the current guide to British life given to people taking the citizenship test:

Baker was Professor of political science at Cambridge, and the pamphlet describes him as 'the son of a working-class home in Northern England,' who 'combines a knowledge of University life with an understanding of the common people, who in our modern democracy, as in the Middle Ages, send many of their best sons to the Universities'. The pamphlet doesn't appear to anticipate the great expansion of higher education that occurred with the new egalitarian values and the baby boom in the 1960s.

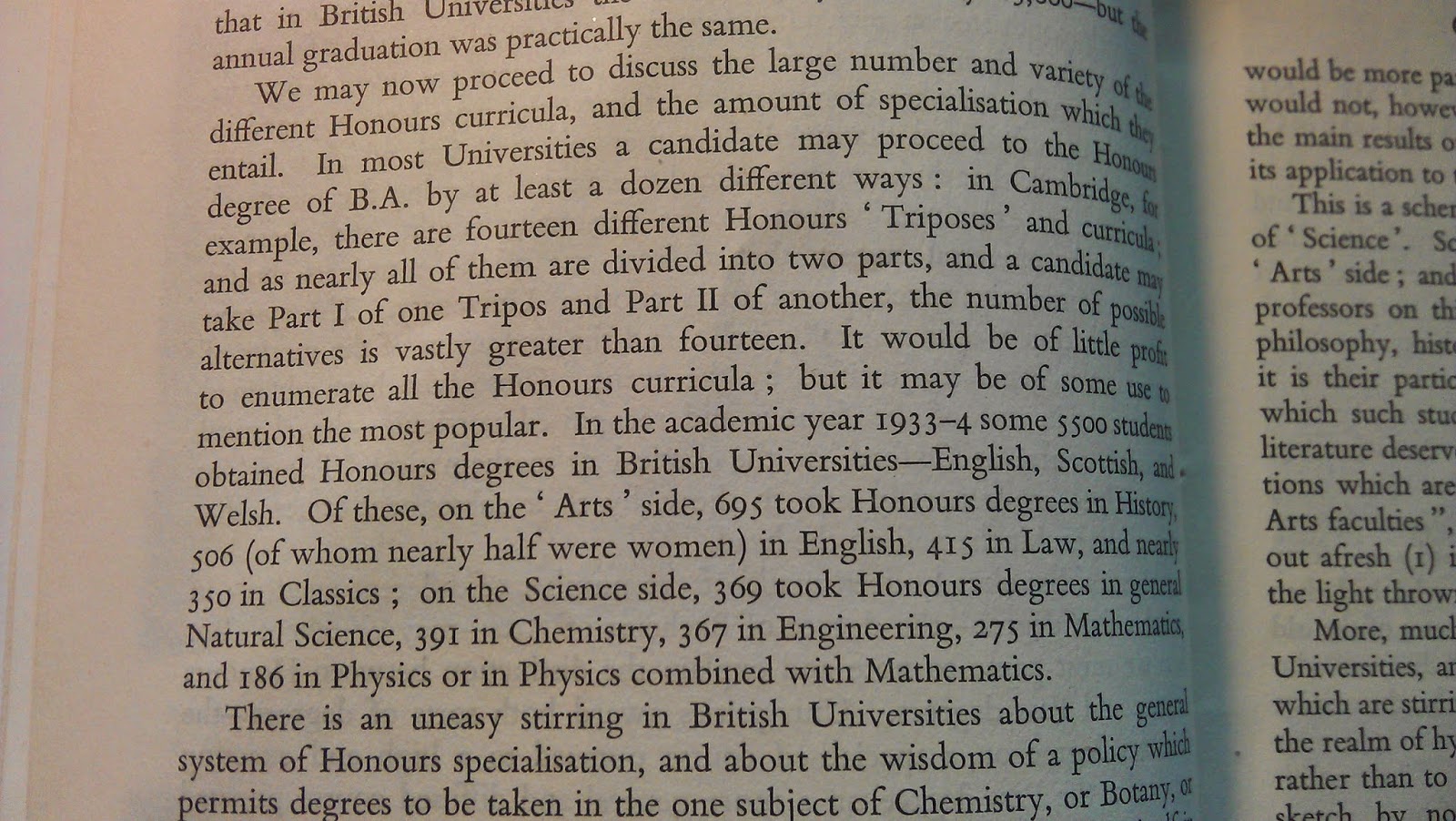

In 1933-4, it states (not sure why it didn't use more recent figures), 5500 students achieved Honours degrees in British universities. Of these, History was the most popular, with 695 students. 506 was English ('of whom nearly half were women') 415 in Law, 350 in Classics. Science comparatively was less popular - 369 in Natural Science, 391 in Chemistry, 367 in Engineering, 275 in Mathematics and 186 in Physics or Physics with Maths.

The next paragraph is perhaps a reminder about current complaints about students specialising too early being 'twas ever thus'.

The role of a scholar is also defended against administrative service - 'it is hard to be a good committee man and a good scholar simultaneously'. External work for government bodies and other committees is seen as a 'distraction', particularly during the War (!).

Notably however, the pamphlet warns that idea that 'research' is 'pure learning' and 'too much emphasised as the shibboleth of a genuine University' at the expense of teaching.

An interesting comment on the growing numbers of female students:

There are some interesting comments on class. It calculated that about 43% of students were on scholarships or bursaries. Also only 20% lived in halls or student lodgings - that apart from Oxford and Cambridge - most students, especially in the Scottish universities - lived at home.

The carefully posed photographs of students studying are fascinating in themselves - so very 1940s, and shiny, clean-cut and impeccably dressed - I suspect they didn't always look like that, and they certainly don't look like the whole range of types of students we have today.

It's a fascinating insight into thoughts about what universities were for, and should be, just after the War, and also how they were promoted to the rest of the Commonwealth. The list of other titles available in the series is also intriguing, and I would love to find more of these pamphlets, especially to compare their language and ideas with the current guide to British life given to people taking the citizenship test:

Baker was Professor of political science at Cambridge, and the pamphlet describes him as 'the son of a working-class home in Northern England,' who 'combines a knowledge of University life with an understanding of the common people, who in our modern democracy, as in the Middle Ages, send many of their best sons to the Universities'. The pamphlet doesn't appear to anticipate the great expansion of higher education that occurred with the new egalitarian values and the baby boom in the 1960s.

In 1933-4, it states (not sure why it didn't use more recent figures), 5500 students achieved Honours degrees in British universities. Of these, History was the most popular, with 695 students. 506 was English ('of whom nearly half were women') 415 in Law, 350 in Classics. Science comparatively was less popular - 369 in Natural Science, 391 in Chemistry, 367 in Engineering, 275 in Mathematics and 186 in Physics or Physics with Maths.

The next paragraph is perhaps a reminder about current complaints about students specialising too early being 'twas ever thus'.

There is an uneasy stirring in British Universities about the general system of Honours specialisation, and about the wisdom of a policy which permits degrees to be taken in the one subject... This uneasy stirring reflects in itself in a demand for what is called 'synthesis'; for some integration of studies; for some attempt to give a general outlook on life, and not merely a dry if accurate knowledge of a single specialty.

The role of a scholar is also defended against administrative service - 'it is hard to be a good committee man and a good scholar simultaneously'. External work for government bodies and other committees is seen as a 'distraction', particularly during the War (!).

Notably however, the pamphlet warns that idea that 'research' is 'pure learning' and 'too much emphasised as the shibboleth of a genuine University' at the expense of teaching.

An interesting comment on the growing numbers of female students:

The presence of women students has probably increased (not by their volition or motion, but simply as the inevitable result of the mixture of the sexes) the volume and the claims of the different social activities.

There are some interesting comments on class. It calculated that about 43% of students were on scholarships or bursaries. Also only 20% lived in halls or student lodgings - that apart from Oxford and Cambridge - most students, especially in the Scottish universities - lived at home.

The carefully posed photographs of students studying are fascinating in themselves - so very 1940s, and shiny, clean-cut and impeccably dressed - I suspect they didn't always look like that, and they certainly don't look like the whole range of types of students we have today.

Comments

Post a Comment