'the historian will be a programmer or he will be nothing'

I've been given a brief for a chapter entitled 'the return of materialism?' for a new book series in cultural and social history, and doing some historiographical research, I read Lawrence Stone's 1979 essay in Past and Present on 'The Revival of Narrative: Reflections on a New Old History'.

In it, Stone bemoans a return to a narrative style of writing history in reaction to the social science methods of research prevalent in the 1960s.

Moreover, what intrigued me more were Stone's points about the then vogue for computational history or 'history and computers' or even 'cliometrics' strike an interesting precedent for the same complaints that are being raised about digital history today

(e.g. see for example, Deborah Cohen's critique and also a reflection by Emily Rutherford, and a mass set of blogs from Birmingham on the much-hyped History Manifesto by Jo Guldi and David Armitage).

Here are some choice quotations from Stone:

The latter quotation was from Le Territoire de l'historien, vol 1.

plus ca change?

edit 25/1:

John Levin (@anterotesis) pointed me to this wonderful example of old-school data history by Alan Macfarlane: http://www.alanmacfarlane.com/reconstructing/contents.htm

This also reminded me of Charles Tilly's quantification project on popular protest meetings on which he based many of his publications, not least Popular Contention in Great Britain, 1758-1834 (1995). This was basically text-mining old newspapers with some basic topic modelling, all done manually by a team of RAs (as Stone above disparages), in the 1980s, an age before digitisation and python enabled historians to do it digitally and semi-automatically.

Tilly's team tabulated a total of 8000 'contentious gatherings' and the language used to describe them in a selection of (admittedly south-eastern) newspapers from a sample of years to find or prove his argument about the progressive development of popular politics in the early nineteenth century in Britain.

Interestingly, he discusses Mark Harrison's critique of his computational methods in relation to the 'nuances' of the sources here (pp. 66-7):

Here is the categorisation of text he used (p.100):

And here are some of the results of his experiment, again pre-dating the current obsession (by Armitage & Guldi et al) with Google N-gram viewer:

I'll leave you to make your own mind up about the validity of his data (my students love picking apart his methodology). But all this does lead to the question about how should we do history - as sole historians using a deep but narrow set of skills, or as teams composed of specialists in lots of fields collaborating for one end product?

In it, Stone bemoans a return to a narrative style of writing history in reaction to the social science methods of research prevalent in the 1960s.

Moreover, what intrigued me more were Stone's points about the then vogue for computational history or 'history and computers' or even 'cliometrics' strike an interesting precedent for the same complaints that are being raised about digital history today

(e.g. see for example, Deborah Cohen's critique and also a reflection by Emily Rutherford, and a mass set of blogs from Birmingham on the much-hyped History Manifesto by Jo Guldi and David Armitage).

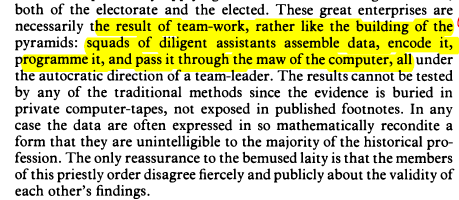

Here are some choice quotations from Stone:

|

| p. 6 |

|

| p.11 |

| p.13 |

plus ca change?

edit 25/1:

John Levin (@anterotesis) pointed me to this wonderful example of old-school data history by Alan Macfarlane: http://www.alanmacfarlane.com/reconstructing/contents.htm

This also reminded me of Charles Tilly's quantification project on popular protest meetings on which he based many of his publications, not least Popular Contention in Great Britain, 1758-1834 (1995). This was basically text-mining old newspapers with some basic topic modelling, all done manually by a team of RAs (as Stone above disparages), in the 1980s, an age before digitisation and python enabled historians to do it digitally and semi-automatically.

Tilly's team tabulated a total of 8000 'contentious gatherings' and the language used to describe them in a selection of (admittedly south-eastern) newspapers from a sample of years to find or prove his argument about the progressive development of popular politics in the early nineteenth century in Britain.

Interestingly, he discusses Mark Harrison's critique of his computational methods in relation to the 'nuances' of the sources here (pp. 66-7):

Here is the categorisation of text he used (p.100):

And here are some of the results of his experiment, again pre-dating the current obsession (by Armitage & Guldi et al) with Google N-gram viewer:

I'll leave you to make your own mind up about the validity of his data (my students love picking apart his methodology). But all this does lead to the question about how should we do history - as sole historians using a deep but narrow set of skills, or as teams composed of specialists in lots of fields collaborating for one end product?

I'd have to suggest the question with which you end has a better solution:

ReplyDeleteAs sole historians using a deep but narrow set of skills AND AND AND as teams composed of specialists in lots of fields collaborating for one end product.